Oldest wine in the world

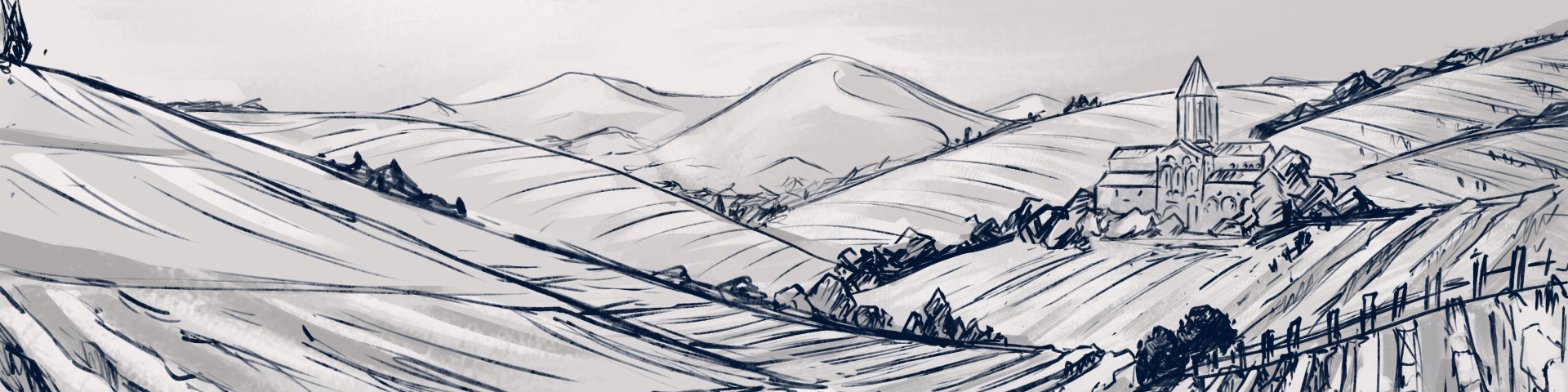

It is in Georgia that the oldest evidence of winemaking has been discovered, with traces of wine found on clay vessels dating back approximately 8,000 years. If we look at the word “wine” itself, the roots of this word can also be traced back to Georgia, where the original term is ღვინო (ghvino).

Georgia has also made a significant contribution to wine classification by introducing a new color of wine—amber (sometimes referred to as orange or, less commonly, copper). Amber wines are produced from white grape varieties, but they gain their deeper flavor, complex rich aroma, and characteristic intense golden color from the process of fermenting the grapes in their entirety after crushing, without separating the juice from the skins and seeds, and often including the stems as well. In other words, amber wine is made from white grape varieties using the production technique of red wine, where the seeds and skins remain in prolonged contact with the fermenting grape juice.

It’s all about qvevri

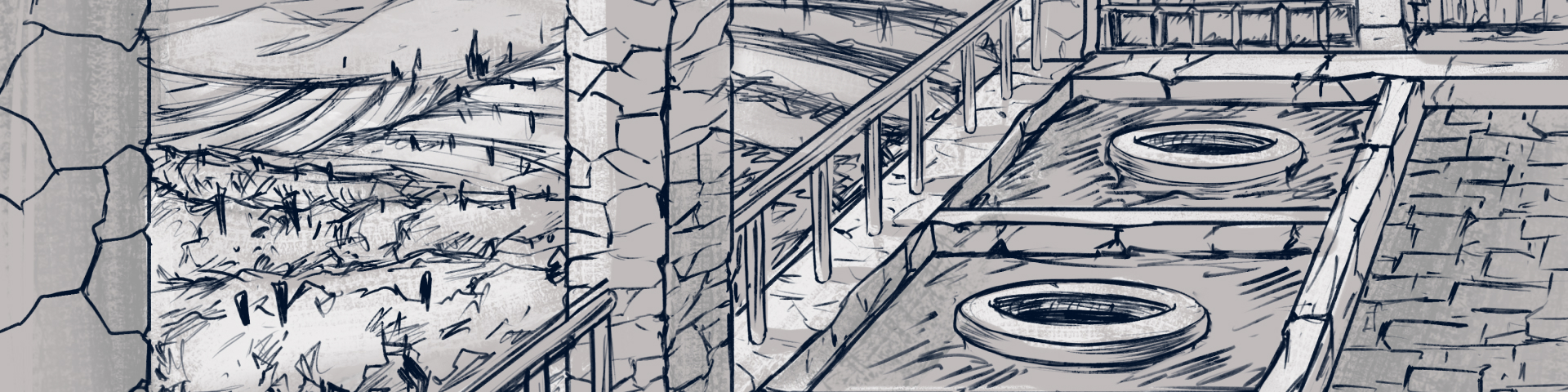

A qvevri is a traditional Georgian winemaking vessel that has been used for thousands of years. The production of wine in qvevris began in the Caucasus around 8,000 years ago, and Georgia is considered the birthplace of this ancient winemaking method.

A qvevri is a large ceramic container shaped like an amphora. These vessels come in various sizes, ranging from small ones holding several dozen liters to enormous ones capable of storing several tons of wine. The clay used to make qvevris is sourced from deposits in Western Georgia and has absolute neutrality toward the wines contained within them. Traditionally, qvevris are buried in the ground, which helps maintain a constant temperature during the fermentation and aging processes.

Hand-harvested grapes are placed in the qvevri along with their skins, seeds, and sometimes stems. This process, known as “skin-contact vinification,” allows the wine to extract more tannins, aromas, richness, and density. Natural fermentation occurs in the qvevri buried in the ground, allowing it to maintain a stable temperature, which is crucial for the consistency of the process. Fermentation can last from several weeks to several months, depending on the grape variety and the desired outcome for the winemaker.

Sometimes, after fermentation, the wine is left in the qvevri for further aging. This stage can last from several months to several years. Here, the earth surrounding the qvevri helps maintain a constant temperature that contributes to the natural stabilization of the wine.

The prolonged contact with the grape skins and the natural fermentation process results in wine with rich flavor, deep aroma, and unique texture—qualities that cannot be achieved by other methods.

As well as that, winemaking in qvevri represents a living connection to ancient traditions and millennia of history. In recent years, interest in wines produced in qvevris has significantly increased. Many wineries around the world have begun to adopt Georgian technology, striving to convey the unique characteristics of their grape varieties that can only be offered by this ancient method. In Georgia, qvevris remain a symbol of national pride and cultural heritage, and the wines produced in them are considered true works of art.

This is more than just a technology; it is a philosophy and a way of preserving ancient traditions. To taste such wine is to touch the history of a great people and the Georgian land. Winemaking in qvevri is the oldest and most authentic method of creating wine that has survived to this day. This method has been recognized by UNESCO as an intangible cultural heritage of humanity, highlighting its significance for global culture and the history of winemaking.

No one country grows as many grape varieties!

Georgia is home to 525 native (autochthonous) grape varieties out of a total of 2,500 varieties that exist in the world. Georgia is a country with a rich winemaking heritage, boasting over five hundred unique grape varieties that grow exclusively within this small nation. This diversity reflects various climatic conditions, soil structures, and ancient winemaking traditions, making Georgian wines special and unique.

Each Georgian grape variety has its own unique history, flavor, and aroma, making their exploration and tasting an engaging and captivating process. Georgian wines are a cultural heritage that conveys a centuries-old connection to the land, traditions, and history. The diversity of Georgian grape varieties opens up endless possibilities for winemakers and wine enthusiasts to create and discover new tastes and aromas, highlighting Georgian wines as true treasures among the wines of the world.

Chacha – the tear of the grape

Chacha, less commonly known as araki, is a strong distillate that is a product of one of the most renowned and distinctive traditions of Georgian winemaking culture. Chacha is a cultural phenomenon that reflects the Georgian spirit of hospitality, the art of distillation, and the rich winemaking traditions of the country.

The name “chacha” translates from Georgian as “pomace” or “press cake,” which relates to the main ingredient used in its production. The distillate is made from the grape pomace left over after wine production, allowing for maximum utilization of the harvest and minimizing waste. The tradition of distilling chacha dates back hundreds of years, and this product is often compared to Italian grappa or French marc; however, chacha has its own unique character, aroma, and flavor.

The production of chacha begins with the fermentation of grape pomace, which includes skins, pulp, seeds, and sometimes stems. After fermentation, this mixture is distilled in copper stills, which helps extract the maximum amount of aroma and alcohol from the raw material. The product can have an alcohol content ranging from 40% to 70%, depending on the region and method of production.

Some types of chacha undergo additional aging in oak barrels, which gives a smoother taste and rich aromas of vanilla, caramel, and oak.

However, traditional chacha usually retains its clear color and clean, bright taste with pronounced notes of grape and a hint of spice.

Chacha holds a special place in Georgian culture. It is served at feasts and celebrations as a digestif and symbolizes hospitality and respect for guests. Georgians believe that chacha has healing properties and often use it as a warming remedy or even a cure for colds. Traditionally, chacha is consumed neat in small shot glasses, accompanied by beautifully crafted toasts that are an important part of Georgian gatherings. Sometimes, chacha is used as a base for infusions and liqueurs with added fruits, berries, and mountain herbs.

Today, chacha is gaining increasing recognition beyond Georgia, becoming a hallmark of the country alongside its remarkable wines. Chacha is not only an important symbol of Georgian winemaking but also a part of the cultural heritage that conveys the spirit, traditions, and centuries-old history of the Georgian people in every drop of this exquisite product.

And now – let us raise a tost!

Georgian wine is a beautiful journey through time and space. We want to share this wonderful journey with you, revealing the combination of millennia-old traditions, natural wealth, and the craftsmanship of Georgian winemakers.

Georgian wines deserve to be known and appreciated all over the world. As the birthplace of winemaking, Georgia offers not only vibrant flavors and aromas of its exquisite wines but also its centuries-old unique history, deeply rooted in culture and traditions. Each glass of Georgian wine reflects centuries of experience, respect for the land, and love for the grape.

We present to you the best Georgian wines, creating an opportunity to discover their unique qualities that can only be found in the sunny vineyards of beautiful mountainous Georgia.

Join us on this wine journey and explore the remarkable Georgian wines—they are sure to become your new favorite discovery!